A Comparative Look at Separationism in China By Jun Kwon and Sung Jang

Ethnic problems involving tensions and conflicts between the majority and minority nationalities within a country are world-wide political issues. Virtually all states are multi-national states and thus have nationality problems. Not only do the problems of ethnic minorities cause social unrest and instability, but also they have the potential to cause bloody conflicts. In recent years, these minority problems are becoming more exacerbated by the rise of ethno-nationalism in many parts of the world. China is no exception. There is no doubt that China is a “unified” multi-ethnic country. Ethnically, China consists of a majority nationality called the Han (漢族) and fifty-five state recognized minority nationalities (少数民族).

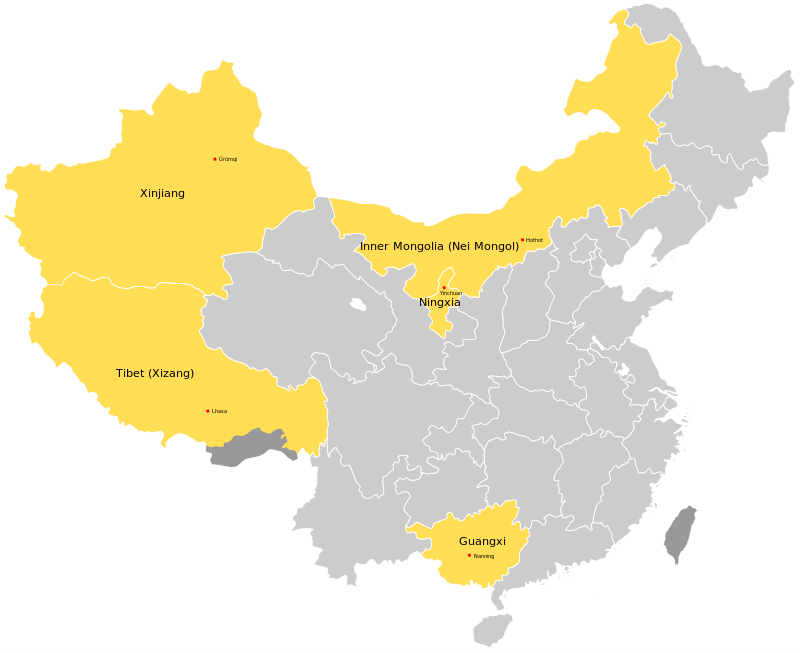

It is no secret that Tibet and the Xinjiang regions have caused a great amount of concern to the central government in China. The indigenous populations of both of these “Autonomous Regions” have long had separationist tendencies. These tendencies have at times become violent revolts in which the Chinese authority has had to crackdown on. Yet Tibet and Xinjiang are not the only autonomous regions in China, but are in fact two of five. The other three autonomous regions of Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Guangxi in China have had little to no separationist tendencies in modern day China.

Photo from Human Rights Watch

First Observations and Questions

The main component of separationism is a strong sense of nationalism. This is not only true in China, but have been so in many countries around the world such as the Catalans and Basque people in Spain, the ethnic Russians in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea, and the Kurds in Turkey, Iraq, and Syria. Much of the nationalism arises from the rejection of a national identity imposed upon them by the states that they are part of. In the case of the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region, the indigenous population is Muslim, and not part of the majority Han-Chinese ethnic group in China. Similarly, in Tibet, the indigenous population practises Vajrayana Buddhism instead of the mainstream Mahayana Buddhism in China, and they have had a long history of being an independent nation-state with few interruptions in between.

Yet when applying this logic of nationalist tendencies to the Ningxia, Inner Mongolia, and Guangxi Autonomous Regions, there is little to no separationist tendencies in these places. The indigenous Hui people in Ningxia are predominantly Muslim; there are ethnic Mongols in Inner Mongolia; and the indigenous Zhuang people in Guangxi are of a different ethnicity and have different religious and cultural practises.

The Indigenous Populations vs. the Han Chinese Population

When comparing these Autonomous Regions side by side, two main divergent variables may explain the separationist tendencies of Xinjiang and Tibet. First, the indigenous populations in Xinjiang and Tibet are in the majority, whereas in the other regions they are the minority. Considering the fact that the Chinese government has implemented policies to have Han-Chinese population transferred into Xinjiang and Tibet, it is likely that the Chinese authorities are aware of this variable. This population transfer of majority ethnicity into regions where there are high levels of separationism has been a method used by states all throughout history as a means of supressing rebellion. A great example of this kind of policy may have taken place in Israeli settlements in the occupied territories like the West Bank. While the political status of Israel and Palestine is complex, the Israeli government has slowly but successfully removed the threat from the indigenous Palestinian population by moving Israeli people into those occupied territories.

Xinjiang and Tibet in Relation to China’s History and Core Territories

Xinjiang and Tibet’s unique situation is also due to their place in Chinese history, or outside of Chinese history to be more specific. The Hui, Mongol, and Zhuang populations had long had interactions with the Chinese empires that existed before modern China. The areas of Xinjiang and Tibet on the other hand had never truly been integrated into China as a core province. When looking at Figure 1, one can see that Ningxia and Guangxi provinces have almost always been within the borders of the Chinese empires. However, this is not the case for Xinjiang and Tibet which had remained outside of the borders of the Chinese polity for most of their history. The only times where both regions were occupied by the Chinese polity was during the short-lived Yuan Dynasty and the Qing Dynasty.

In the case of Inner Mongolia, while one can see that significant part of it is outside the borders of many of the Chinese dynasties, the Mongols experienced sinicization during the Yuan dynasty when Kublai Khan adopted many Chinese traditions to rule it. The situation is similar to the Manchurians too where the Qing dynasty adopted many Chinese traditions and beliefs in order to rule China. In essence, the two foreign ruling dynasties of China that were not ethnically Han-Chinese chose to integrate themselves into the local culture of China, rather than forcing theirs on the local population.

As such, when looking at Xinjiang and Tibet, one has to consider that both geography and the lack of cultural and political integration into China are what makes these areas peripheral and separationist from the modern Chinese nation. As Xinjiang and Tibet were and are not part of the Chinese civilization having long remained outside it, they have resisted the attempts of forced integration.

Jun Kwon is Chair of International Studies and Assistant Professor of Government at Utica College

Sung Jang is a government student at Utica College.