Trump’s crash course in national security by Austen D. Givens

The Trump administration is fast learning the ropes of American foreign policy and national security.

President Trump’s Executive Order blocking immigrants from a handful of Muslim-majority nations and suspending the Syrian refugee settlement program triggered an avalanche of well-deserved criticism and a formal judicial reprimand from the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, for instance.

But President Trump also increasingly appears to be taking the hewn path of past Republican presidents.

Contrary to his flame-throwing campaign rhetoric, Trump is sending signals that he will act decisively against longstanding U.S. adversaries and preserve defense alliances with American allies abroad. That is cause for guarded optimism, particularly among conservative foreign policy professionals, who have until now recoiled in horror at the Trump machine.

Take Russia. On Valentine’s Day Mr. Trump accepted the resignation of his mercurial National Security Advisor, Michael Flynn, who was embroiled in allegations that he colluded with the Russian ambassador to the United States over economic sanctions against Russia. Significant questions remain about the depth and extent of ties between the Kremlin and the Trump White House. (Full disclosure: I’ve raised some of these questions myself.)

Trump himself has repeatedly said that he would like the United States and Russia to collaborate more. Yet Flynn’s resignation shows that his ties to Russia were increasingly a political liability for Trump. If this trend continues, the DC-Moscow “grand bargain” Trump envisions may not come to pass.

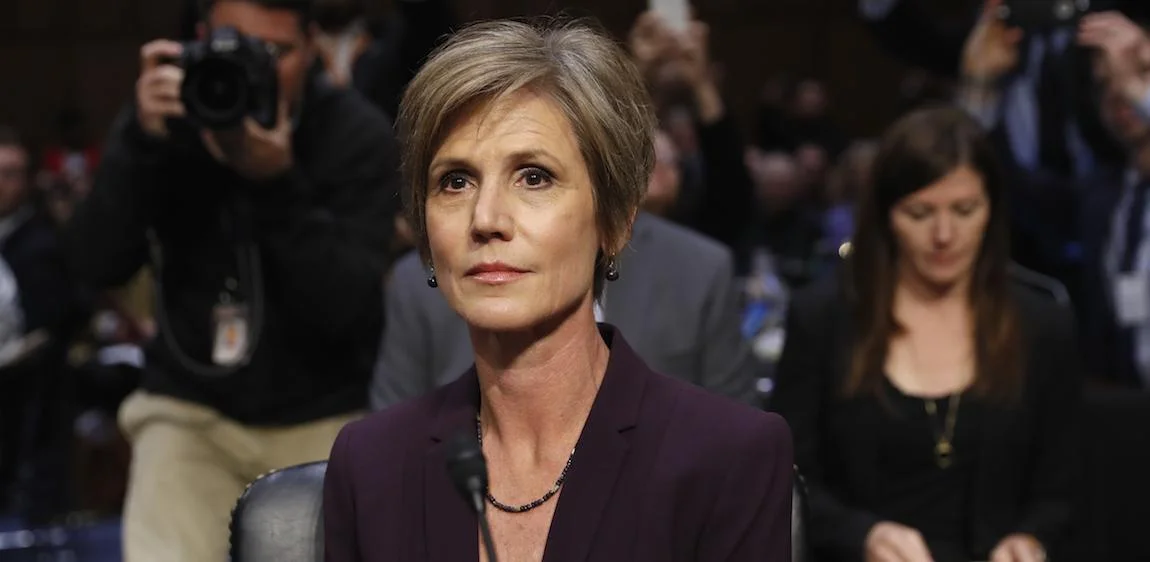

Photo by Chip Somodeville/Getty

Or take North Korea. During an official state visit over the weekend, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and President Trump scrambled to respond to news that Pyongyang had fired a ballistic missile toward Japan. At a news conference with Abe, Trump underlined that the United States stood with its ally, Japan, “100%.” This show of solidarity struck a dissonant chord from Trump-the-candidate, who yelled that Japan was not paying its fair share in exchange for its presence beneath the U.S. defense umbrella in Asia.

Or consider Iran. After the Iranian military fired a medium-range missile on February 1st, the United States imposed new sanctions on 25 individuals and businesses connected to the Iranian regime. Tehran knew precisely what it was doing in firing the missile—testing the Trump administration, and with it, the international community. The White House’s response, though, was similar to responses during the Obama administration and George W. Bush administration, which each imposed financial sanctions on Iranian entities to punish what they viewed as hostile, uncooperative behavior.

It is too early for conservative foreign policy professionals to cheer for President Trump. The White House’s unwavering commitment to implementing an immigration and refugee ban of some variety is a moral outrage, and stands to severely harm U.S. national security interests. But there are at least a few signs that Trump-the-President’s approaches to foreign policy and national security may be closer to those of Reagan than Trump-the-candidate.

Austen D. Givens is Assistant Professor of Cybersecurity at Utica College.